Expert analysis

12 November 2019

Is it safe to return home? New research unpicks repeated displacement in South Sudan

As the deadline for the formation of South Sudan’s unity government comes and goes, new research from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre reveals the drivers and patterns of repeated forced displacement within the country and across borders.

Under the terms of the latest peace agreement which aims to put an end to South Sudan’s almost six-year civil war, the warring political parties had until 12 November to form a unity government. As the deadline loomed, many feared the country would descend once more into bitter conflict owing to outstanding disputes. Already delayed since May, the president and a former rebel leader agreed to set aside one hundred days more to address these unresolved issues; much to the relief of everyone involved in the political mediations.

The success of this coalition, now scheduled for February, will have a significant impact on the stability of the world’s youngest nation. Should the power-sharing deal fail and the current ceasefire collapse, renewed violence could displace hundreds of thousands of people in the country. If it holds and the security situation improves, millions could return home.

“We decided to return to South Sudan because of the peace agreement, but its implementation is still in process and we’re unable to go back home for fear that the war might break out again … so it’s better to stay here."

– A returning refugee from Ethiopia in Juba Protection of Civilians (POC) site

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) estimates that almost 1.9 million people are living in internal displacement in South Sudan, and close to 2.3 million have sought refuge from the conflict in neighbouring countries.

Against this backdrop of instability, insecurity and mass displacement, IDMC has published a new report exploring the relationship between internal displacement, cross-border movements and the conditions of return. It is part of IDMC’s ‘Invisible Majority’ thematic series and is based on more than 200 interviews in Bentiu and Juba.

Repeated internal displacement

The findings show that many people in South Sudan have suffered repeated internal displacement, returning during relatively peaceful periods only to flee again when the fighting resumes. More than three quarters of the research participants for this study said they had been displaced more than once.

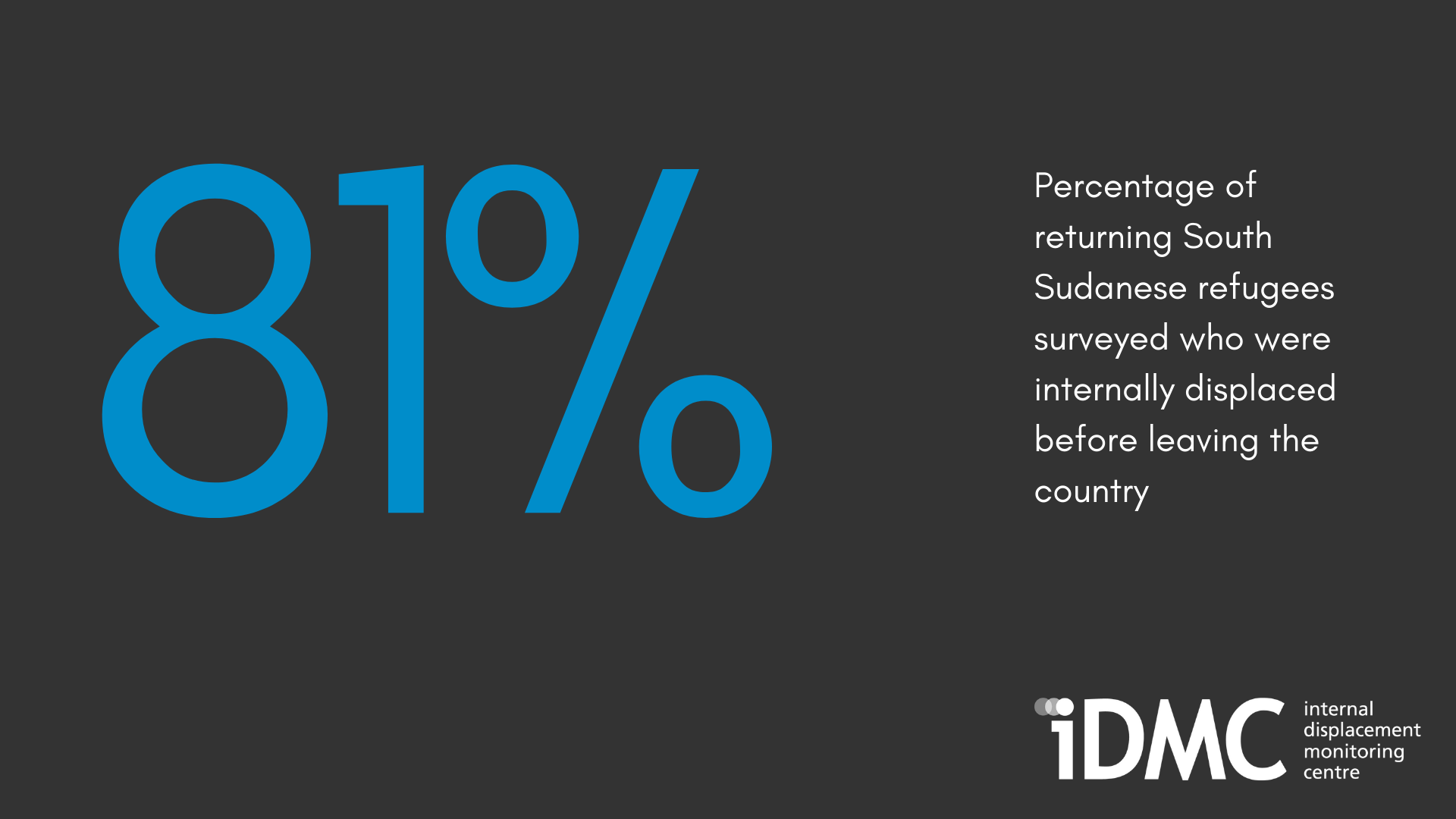

If it’s safe and they have the resources, some people choose to flee across a border. Many, if not most, refugees start their journeys as internally displaced people (IDPs), and conversely many returning refugees face the risk of internal displacement again. More than 80% of the refugees surveyed had been internally displaced before they left the country, half of these more than once.

Motivations for returning home

The study also revealed that improved security is not the only factor behind people’s decision to return. Poor living conditions in their host community, a lack of livelihood opportunities and reunification with family and friends were also important motivations to return home. In some cases, return was not voluntary but forced. Particularly in Sudan, respondents said the security forces had forced them to leave or threatened them with arrest and deportation.

“I wouldn’t have returned if it hadn’t been for the threats […] that arose from the Sudanese protests. The situation here is still far from normal.”

– A returning refugee living in a temporary shelter in Rubkona

Returning to displacement

When refugees do return, many end up back in displacement. Some do not return to their areas of origin due to ongoing insecurity. Two-thirds of the returning refugees surveyed were living outside their area of origin. More than 80% of the IDPs surveyed had property before their displacement, but 70% of these said it had since been destroyed.

Poor return conditions

The research found that many returnees do not have access to water, basic services or livelihood opportunities, leaving them with considerable needs. Throughout South Sudan, about 2.2 million school-aged children currently receive no education. Among the respondents, 85% of IDPs said there were too few teachers, and 80% complained about the quality of education.

The recurrent waves of conflict have crippled South Sudan’s economy. The inability to farm and disruption to markets have fuelled widespread food insecurity. IDPs’ main source of income is day labour and more than a third of the research participants said they found it difficult to get by.

“We depend on NGOs’ food assistance […] Women collect firewood to sell for survival. Some wives are divorcing because their husbands no longer have the means to take care of them.”

��– An IDP in Bentiu POC

Uncertain future

Extending the deadline for the formation of the unity government has likely prevented another outbreak of conflict, which would have led to yet further internal and cross-border displacement. We will find out in February if peace is on the cards for the next chapter in South Sudan’s future. Even if a coalition is formed, however, many more obstacles will need to be passed before people can expect a lasting and dignified solution to their displacement.

Beyond the insecurity posed by the current political impasse, reliable access to food and to livelihood opportunities, basic services and adequate standards of living remain elusive to many South Sudanese. To overcome these obstacles, humanitarian, peace-building and development actors will need to show they can work together. Until they do, returns will continue to be premature. As the political negotiations continue, one thing must be prioritised above all else; displaced and host populations must be protected.

“If the UN leaves us with no protection, then I will become a rebel or go to another country as a refugee.”

– An IDP in Juba POC